last modified: 2017-12-27

Front page

Author: Clement Levallois

emlyon business school. 23, avenue Guy de Collongues, 69130 Ecully, France

+33(0)4 78 33 77 25

The final publication is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-017-9491-x

Acknowledgments: I wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for useful suggestions. I gratefully acknowledge the kind assistance of Lizette Royer on the archives of Frank Beach, J. Paul Scott and T. C. Schneirla at the University of Akron. The intellectual stimulation of Philippe Fontaine is deeply appreciated. All remaining errors are mine.

Keywords: social behavior; animal behavior studies; sociobiology; Edward O Wilson; ethology; comparative psychology; ecology; JP Scott; Stuart Altmann

Abstract

This paper aims at bridging a gap between the history of American animal behavior studies and the history of sociobiology. In the post-war period, ecology, comparative psychology and ethology were all investigating animal societies, using different approaches ranging from fieldwork to laboratory studies. We argue that this disunity in "practices of place" (Kohler 2002) explains the attempts of dialogue between those three fields and early calls for unity through "sociobiology" by J. Paul Scott. In turn, tensions between the naturalist tradition and the rising reductionist approach in biology provide an original background for a history of Edward Wilson’s own version of sociobiology, much beyond the William Hamilton’s papers (1964) usually considered as its key antecedent. Naturalists were in a defensive position in the geography of the fields studying animal behavior, and in reaction were a driving force behind the various projects of synthesis called “sociobiology”.

Introduction

In the immediate post-WWII period, animal social behavior was investigated by several overlapping scientific communities, at the frontier between biology and psychology. Ecologists, ethologists, and comparative psychologists represented distinct research traditions, ranging from naturalists to white-coat laboratory workers and blackboard mathematicians – leading to widely divergent representations of how “social” behavior in animals was to be accounted for.

Working in very different settings, both indoor and outdoor, these students of animal behavior interacted via key individuals and episodic debates, alternating between conflicting attitudes and calls to reach a synthesis. Against this background, Edward O. Wilson’s sociobiology, while similarly devoted to “the systematic study of the biological basis of all social behavior” (Wilson 1975, 4), is often conceived by the historiography as a relatively separate and later development. The goal of this paper is to flesh out the relation between sociobiology and the contemporary established fields studying animal social behavior in post-WWII America.

The result is a narrative where the history of sociobiology is woven with the history of ecology, ethology and comparative psychology. We identify the naturalists (and their concerns about animal behavior studies performed in the field) as a driving force in what became the sociobiological synthesis. Shifting attention to the various issues the naturalists' debates animated provides a richer understanding not just of sociobiology’s formation but also of animal social behavior and of the subsequent history of post-1950s biology.

An attempt to write the history of sociobiology is bound to be surrounded with ambiguity: is it to be the history of a field, a term, or even a book? Some reviewers of Wilson’s Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (Wilson 1975) suggested that the title of the book accomplished a performative act. Because it was a new label, with a definition attached to it, and a 697-page book embodying its principles, a new field called “sociobiology” would have thence been created in 1975 [1]. Alternatively, one could consider that sociobiology, being defined by Wilson as the investigation of the biological origins of social behavior, was a subject with a history at least as old as Darwin’s Descent of Man (1871) – rendering the history of so large a topic very diluted, and the origins of the label “sociobiology” relatively unimportant [2]. One could still choose to see sociobiology as mere réchauffé of late nineteenth, early twentieth century “social Darwinism,” because of its potential or actual conservative implications (Cherry 1980; Lerner 1992).

However, most usually concur with Ullica Segerstrale’s sociological account of the sociobiology debate, which considers that the “deep background” of sociobiology lays in the mid-1960s with William Hamilton’s and Robert Trivers’s articles on the evolution of altruism (Hamilton 1964; Trivers 1971; Trivers 1974) – a narrative at odds with Wilson’s own view. [3]

These narratives leave a rich trove of materials unaddressed, worth incorporating in a history of sociobiology: the development through the 1950s and beyond of several disciplines claiming an interest in the biological study of the social behavior of animals, paving the way to initiatives named “sociobiology”, well before Wilson’s use of the term. To the point, we claim that post-WWII animal social behavioral studies (ethology, comparative psychology and the Chicago school of ecology) were in a state of protracted conflict over their different traditions of indoor and outdoor studies. Wilson’s sociobiology, we will argue, can be profitably reconsidered as one of a series of attempts to resolve those tensions by defending the naturalist tradition in animal studies.

Recent works examining the field-laboratory border in twentieth century biology have emphasized the role of localization in the shaping of biologists’ practices, leading to very different styles of research and career paths depending on whether they worked in the field, a zoo, a museum or in the laboratory (Livingstone 1995; Weidman 1996; Finnegan 2008; Lightman 2016, 179–328). [4] Typically, since the late nineteenth century, field biologists struggled to retain a sense of legitimacy at a time when standards of quantification and control elevated the laboratory and experimental science as the imagined future of biology (Benson 1991). Naturalists adapted techniques from the laboratory to the use in the field, developed their own tools, and invented protocols to reinvent the field as a place where “nature experiments” could be performed. These activities which necessitated new capabilities, such as field stations, transformed the traditional, observational natural history into “professional” ecology in the early decades of the twentieth century (Billick and Price 2010; Kingsland 2010). We argue that these tensions continued to play a role in post-1950 biology, and even heightened due to the coming of age of yet another mode of production of knowledge in contemporary biology, namely blackboard mathematical biology.

We will first depict the three main traditions of investigation of animal societies (ecology, comparative psychology and ethology), examining how they were situated at different places in the geography of scientific practices in mid-twentieth century, leading to divergent and equally problematic conceptions of the nature of “social” behaviors, and the methods to study them. We will then make the argument that this lack of unifying framework led outdoor biologists, who in this geography suffered from a recurring deficit of scientific credibility, to seek closer relations with experimental biology in order to develop an alliance, that behavioral geneticist J. Paul Scott called “sociobiology”. Once established that Scott’s sociobiology first emerged in the 1950s as a synthesis of laboratory and field based practices, it will be recognized that a similar pattern explains the forging of alliances by naturalists with mathematicians and theoretically minded biologists in the 1960s, resulting this time in Stuart Altmann’s and then Wilson’s sociobiology. This will lead us to reconsider in a last section the meaning of Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, and to suggest that this project led to reaffirming the naturalist credo in biology.

Troubles on the Lab-Field Border

Until the 1950s, ecologists at the University of Chicago were among the most visible students of social behavior in animals (Mitman 1992). [5] Drawing on a tradition of attention to the relationships between the organisms and their environment, students of animal behavior at the Department of Zoology emphasized the social relations in animal communities. The physiological gradients conceptualized by Charles M. Child, Ralph Gerard’s notion of “orgs” encompassing both living beings and societies, Alfred Emerson’s attachment to the concept of superorganism, and Warder C. Allee’s stress on the adaptive role of cooperation in evolution were as many ways to think of animals not as a homogeneous collection of isolated individuals, but as integrated groupings (Mitman 1992). [6] According to the definition of the “social” held at Chicago, the behavior of individual animals was to be explained as part of a subsuming whole functioning like a coherent system or organ, displaying physiological properties (Burns 1980; Banks 1985; Mitman 1992).

Interestingly, those integrated groupings were given different names and treatments, depending on the “practices of places” (Kohler 2002) used to investigate them. Social groups in nature were “communities”, while they were “populations” when studied in the labs, or in the field but with standards of quantitative rigor meetings those of the lab (Allee et al. 1949, 265). The problem at Chicago was that they tended to attach as much if not more importance to the field as to the laboratory, at a time when funding was re-orientated towards a physics-inspired biology, designating clearly the laboratory as the preferred place to conduct science. [7] Indeed, Emerson, Allee and their colleague Karl Schmidt were especially keen on field work: “seasoned tropical biologists”, they all “shared a certain fondness for life in the jungle.” (Mitman 1992, 103) Allee lamented that he “want[ed] students with a love for field work which even the handicap of living in the city of Chicago cannot quench.” “I am tired of working with man-made, degree-hunting graduate students in zoology. I welcome the natural naturalist who cannot be kept out of field work even though his doctor’s or other research lies elsewhere.” (Allee 1930, 630).

This attitude also translated into the debates on the levels of selection in evolutionary theory. Some among the younger generation of students reacted negatively to the “good of the species” brand of argument which was commonplace among naturalists. Based on statistical analyses of homogeneous populations in labs, rather than in the field, the renunciation to its fitness by the individual for the benefit of a community was judged a logical impossibility. “If it was biology Emerson was discussing, I would be better off selling insurance,” recalls evolutionary biologist George Williams about his attendance to a conference at Chicago in 1957 (Brockman 1995, 40). In sum, Chicago ecologists were situated right on the border between the field and the laboratory, which put them in an unstable position. While they studied populations in the laboratory as a complement to the investigation of natural communities in the field, the new biology used the laboratory to cancel the noise of social interactions and isolate the evolutionary destiny of homogeneous, asocial populations.

In contrast, the immense majority of comparative psychologists conducted their science indoor, which spared them the legitimacy issues faced by field ecologists. But their definition of “social behavior” turned out to be equally problematic, though in a different way. Whereas ecologists at Chicago worked in the field and in the laboratory, the privileged techniques and location of comparative psychology were quasi-exclusively those of the laboratory, affording a tight control of environmental parameters and precise measurements. This rigor was contrasted with the perceived unscientific, subjectivist methods of field biologists, whose outdoor activities could allow neither the full description nor the reproducibility of observations.

Most contributions in comparative psychology reported experiences of individual animals engaged in exercises of maze-learning or sensory discrimination under various stressful conditions. Individual behavior was understood as a manifestation of the subject’s inner physiological drives, susceptible of modification through physiological manipulations and conditioning (via reinforcement or punishment). In the relatively rare instances when social behavior was under scrutiny, comparative psychologists proceeded by replicating their methodological approach to the study of single animals. [8] This approach to social behavior, by comparing the “normal” social trait with highly perturbed states, was conducive to a peculiar understanding of sociality and behavior. Indeed, comparative psychologists regularly expressed their wish for sounder theoretical motivations to their scientific enterprise, looking at ethology alternatively as a potential inspiration for reform, and as a threatening competitor. [9]

In comparison with the experimental approach to the study of social behavior privileged by comparative psychologists, the defining feature of ethologists has sometimes been said to be that they loved the animals they studied (Dewsbury 1992, 209; Burkhardt 2005, 312). Ethology achieved international scientific standing in the post-war period with the works of Dutch Niko Tinbergen and Austrians Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz. Contrary to comparative psychologists, ethologists did not try to identify the physiological origins of social behavior with laboratory experiments, followed by dissections and physiological analyses. Instead, they claimed the merits of considering a rich variety of species and the importance of spending long hours at animal watching, so as to surely identify the original, “untouched” behaving of animals. Focused on the full range of behavior rather than on the functioning of high level cognitive abilities, ethologists downplayed the importance of learning and insisted on the instinctual, innate patterns of behavior. [10]

Natural or semi-natural settings obviously allowed for an increased attention to social behavior. In open fields and with free movements, phenomena like imprinting, gregariousness, mating, conflict or cooperation were more readily observed than by confining single animals in mazes or Skinner boxes. [11] Yet, the import of ethology in the United States did not go without concerns for its scientific credentials. Comparative psychologists were quick to point to their relative strength in quantitative methods, and to dismiss the ethologists’ too strong insistence on the innate nature of animal behavior, to the detriment of an attention to the development and learning stages, necessary for the individuals to acquire their full pattern of behavior. [12]

This categorization of animal behavior studies circa 1950 in three currents (ecology, ethology, comparative psychology) has sometimes being criticized for its arbitrariness, since a number of individuals tried to render them interfecund, leading to exchanges of concepts, techniques, and to common publications (Dewsbury 1992). Some comparative psychologists did conduct field studies, and some ethologists had a preference for observations in semi-natural conditions, rather than in the complete wilderness. [13] We contend here that distinguishing the features of these fields, while acknowledging the influences and overlap between them, does not impede our comprehension of animal social behavior studies at the time. To the contrary, identifying the tensions between these fields, in particular the long standing competition for scientific credibility between naturalist and laboratory-based traditions, is key to the understanding of the recurrent calls to synthesis in animal behavior studies in the 1950s and beyond. Often presented as idiosyncratic projects (as in “Wilson’s sociobiology”), we want to re-present them now as responses to a common need: building up legitimacy by making alliances between the laboratory and field research traditions.

The Committee for the Study of Animal Societies under Natural Conditions

The first use of the term “sociobiology” in the post-war period nicely illustrates the attempts for the three traditional fields investigating the social behavior of animals to communicate on a common platform. In 1946, a conference sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation was convened at the Jackson Memorial Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, under the supervision of behavioral geneticist J. Paul Scott (Paul 1998). Scott had the profile to be a go-between for the three fields. A former student of Allee and Wright at Chicago, he had demonstrated an interest both for field and laboratory studies. Working on organisms ranging from fruit flies to mammals, and director of behavioral studies in the national center for the production of laboratory rats, he was well-prepared to act as a synthesizer of various approaches to animal behavior studies. Indeed, if the conference on “Genetics and Social Behavior” was supposed to launch a Rockefeller project to demonstrate the genetic basis of intelligence, Scott and the participants “hijacked” the conference and made it deliver an unexpected outcome (Scott 1985; Scott 1989). [14]

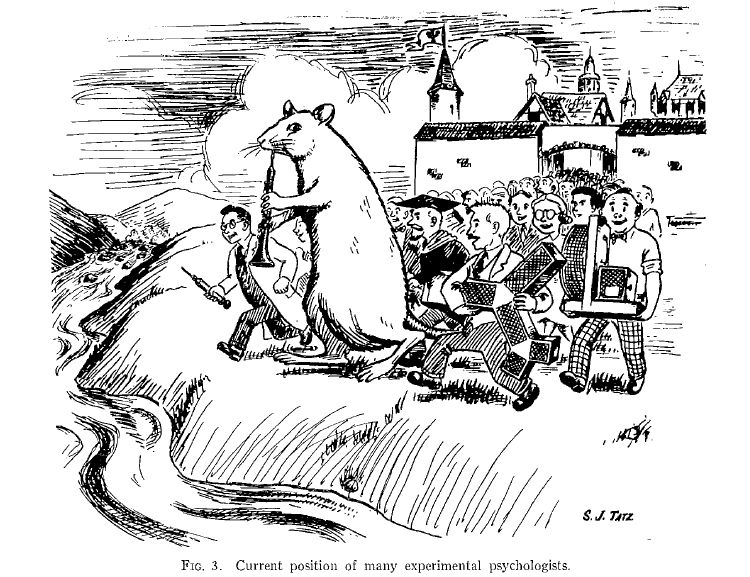

The audience gathered a sample of scientists from ecology and comparative psychology, sympathetic to a dialogue of their fields with ethology. Hence, the comparative psychologists in attendance were notable for having expressed an unusual interest in the study of animal behavior under natural conditions, rather than in their familiar laboratories. Robert Yerkes, who chaired the conference, was the towering figure of comparative psychology, and came from a time when the discipline used many more animal models, in a variety of settings. [15] C. R. Carpenter, a former fellow of Yerkes’s “monkey farm”, was also among the audience. He was praised by Scott who had an enormous respect for his work on the howling monkeys, stressing that it was “the first major study of mammalian society under natural conditions.” (Carpenter 1934; Scott 1985, 414). The audience also comprised two other figures in comparative psychology, both in the forefront of the criticism of the overwhelming position of laboratory studies in their field. Frank Beach, Curator of the Department of Animal Behavior at the American Museum of Natural History until this year, was receptive to Tinbergen’s ethological approach to animal behavior studies, and would address a scathing criticism of comparative psychology as performed by its flagship journal, that he suggested should be renamed “The Journal of Rat Learning” (see Figure 1) [16].

T.C. Schneirla was the other prominent comparative psychologist present at the conference with also a strong interest in field studies. Specializing in ants, he had co-authored a classic textbook in comparative psychology replete with studies of rat maze learning, but had also published an acclaimed study of army-ants, observed in the field in Barro Colorado Island in 1932 and 1936 (Schneirla 1933; Maier and Schneirla 1935; Schneirla 1938; Tobach 2000) [17].

Reflecting the participants’ pluralistic approach to the study of social behavior, the Bar Harbor conference called for a conjoint development of field and laboratory studies. An outcome of the conference was the creation of a “Committee for the Study of Animal Societies under Natural Conditions” (CSASNC) to translate this goal into practice. By wedding the best practices of comparative psychologists to those of the naturalists, the result would be a synthesis “between the fields of biology (particularly ecology and physiology) and psychology and sociology.” “Many names have been given to it, but perhaps the best and most descriptive is ‘sociobiology’,” Scott indicated at the first conference organized by the CSASNC (Scott 1950, 1003–1004).

This blend of practices would need a suitable place to flourish, at mid-range between the laboratory and the complete wilderness. Island biological stations fitted these constraints. Straightforwardly, insularity meant that one of the great features of the laboratory, isolation, was reproduced in preserved natural settings – without the artificiality of man-made walls and cages. Precise census work could then be performed, opening the way to demographic measurements and controlled manipulations of the structure of social groups. Hence, the CSASNC urged that Barro Colorado Island should “be put on a permanent basis of support as a center of tropical research” (Scott 1947, 208). Islands would also play a crucial role in the genesis of Altmann’s and Wilson’s versions of sociobiology [18].

The CSASNC acted as a provider of resources for the informal network of naturalist minded students of animal social behavior. Through a typed newsletter sent regularly by Scott, CSASNC members and “correspondents” were told about available grants, places suitable for naturalistic study, and job openings [19]. The newsletters also performed an organizational function, several including a listing of members and correspondents, or serving as call for papers and programs for the yearly meetings of the CSASNC. Sub-committees were created to collect a bibliography on field instruments, or to encourage field trips to Barro Colorado Island. In 1948, the first conference of the CSASNC in New York led in 1950 to the publication of papers on the “Methodology and Techniques for the Study of Animal Societies,” edited by Scott. This collection provided the first elements of a synthesis between laboratory and field studies. Field workers showcased an updated toolbox for outdoor studies, demonstrating a conciliatory attitude towards laboratory studies [20]. In Scott’s perspective, sociobiology was to be the organizational vehicle through which naturalists could gain a renewed visibility for field work, at a time when they felt academic journals were becoming less open to this type of research:

All of this [the activities of the CSASNC], I think, will tend to work in the direction of both building up interest in animal behavior and sociobiology and thereby making it possible to do what we talked about at the [New York] conference, namely to organize a new journal for this type of work. In spite of the cordial attitude of the editors of various existing journals, my own experience and that of others who have worked in the field leads me to believe that it is often very difficult to fit papers to the individual requirements of these journals.

Scott to Schneirla - July 9 1948 - Box M579 - Folder “Conferences: Behavior Committee” Schneirla papers.

Hence sociobiology, as it was first coined and developed by the CSASNC, arose as a form of appeasement to contemporary tensions between field and laboratory studies in animal social behavior studies. It was adamant that the naturalist tradition was an asset rather than a hindrance for the scientific study of animal behavior. The task for sociobiology was precisely to develop a rigorous approach to field studies in order to match the methodological rigor expected by biologists working in the laboratory. This striving for an alliance between naturalists and their colleagues working indoor was at the core of Scott’s sociobiology, as it would be in Altmann’s and Wilson’s.

Through the late 40’s and 50’s, the CSASNC adopted a more and more formal structure and it became a regular feature of the joint annual meetings organized by the Ecological Society of America (ESA) and the American Society for Zoology (ASZ) to sponsor a session on “Animal Behavior and Sociobiology.” In 1956, a “Section On Animal Behavior and Sociobiology” was eventually created within the ESA, and it gained more than 300 members in less than a year [21]. It is at this point that the young Wilson established contact with this new current of animal social behavior studies, via his student Altmann.

Primatology on Cayo Santiago: Sociobiology, Redux

In Fall 1953, two years into his graduate studies at Harvard, Wilson had attended a conference by Tinbergen and Lorenz on an American tour, who were lecturing on the “new science of ethology” (Wilson 1994, 285) [22]. Lorenz, the passionate naturalist and animal-lover, made a decisive impression on the similarly inclined Wilson:

Then Lorenz came … He was a prophet of the dais, passionate, angry, and importunate. He hammered us with phrases soon to become famous in the behavioral sciences: imprinting, ritualization, aggressive drive, overflow; and the name of the animals: graylag goose, jackdaw, stickleback. He had come to proclaim a new approach to the study of behavior. Instinct had been reinstated, he said; the role of learning was grossly overestimated by B.F. Skinner and other behaviorists; we must now press in a new direction. He had my complete attention. Still young and very impressionable, I was quick to answer his call to arms. Lorenz was challenging the comparative psychology establishment. … My thoughts now raced. Lorenz has returned animal behavior to natural history. My domain. Naturalists, not psychologists with their oversimple white rats and mazes, are the best persons to study animal behavior.

Naturalist (1994) pp. 285–287 - italics in the original

Wilson was not aware that his feelings against “rats and mazes” comparative psychology and behaviorism, or his enthusiasm for naturalist studies, were particularly close to those of the CSASNC members [23]. But he did not remain isolated for long. In 1955, Wilson had just finished his Ph.D. dissertation on the ant genus Lasius when the Harvard administration asked him to supervise a post-graduate student, one year younger than him.

This student, Stuart Altmann, had specialized in the study of social behavior of rhesus macaques, and had thereby developed strong connections with the primatologists involved in the CSASNC [24]. Carpenter had given Altmann the census data of another colony of rhesus monkeys he had implanted himself in the late 1930s on Cayo Santiago Island, off the coasts of Puerto Rico. In the 1940s, the biological station of Cayo Santiago had suffered a lack of funds, interrupting census work while the population of monkeys was decimated by shortage of food and removals for civil and war-related research (Rawlins and Kessler 1986, 29). In 1956, behavioral research on social primates resumed with Altmann traveling to Cayo Santiago, his doctoral supervisor Wilson accompanying him:

My interest in sociobiology was not the product of a revolutionary’s dream. It began innocently as a specialized zoology project one January morning in 1956 when I visited Cayo Santiago, a small island off the east coast of Puerto Rico, to look at monkeys. … The two days Stuart [Altmann] and I lived among the rhesus monkeys of Cayo Santiago were a stunning revelation and an intellectual turning point … In the evenings Altmann talked primates and I talked ants, and we came to muse over the possibility of a synthesis of all the available information on social animals. A general theory, we agreed, might take form under the name of sociobiology [25].

Naturalist (1994) pp. 308-310

The naturalist approach was still at the heart of this envisioned sociobiology, as Altmann’s starting point was the collection over two years of ethograms and measurement of frequencies of behavioral displays in the wildlife of Cayo Santiago. However, as in Scott’s case, what would be constitutive of sociobiology was the wedding of typical naturalist practices with those from “indoor” biology, as a means to overcome the deficit of credibility of traditional naturalist studies. Hence, Altmann did not rely on the notion of “releaser” as he did for the concept of ethogram, considering that it would introduce “gratuitous” assumptions on the sequential orders of behavioral patterns (Altmann 1965). He would have them better ascertained from scratch by a sociometric analysis, demanding skills borrowed from statistics [26].

On top of the blending of different methodological traditions to collect and establish the empirical validity of field observations, Altmann and Wilson considered that an improved theoretical framework was necessary to extend the lessons from this case study of a single animal society to a comparative study of all social behaviors in animals. Altmann’s own preference was with a cybernetic approach to communication. Looking for an elementary language able to univocally describe the wealth of social networks existing across species, he came to the view that the theory of information and communication, as developed by Norbert Wiener, was such a tool (Altmann 1962; Altmann 1965; Altmann 1967; Haraway 1981) [27].

This signaled an important shift in animal behavior studies, with the field and the laboratory being now supplemented by an additional legitimate place of production of knowledge: the blackboard. Conclusions derived from the development of mathematical models, traced on a blackboard by a researcher with possibly no prior training in zoology – and more probably in physics or engineering, would gain greater and greater credit, in a remarkable and rapid shift from the situation of the last years (Keller 2002, 79–89). At first, Wilson followed a route similar to Altmann’s, relying on the concept of feedback loops and the formalism of information theory when analyzing mass-foraging in ant societies (Wilson 1963; Haraway 1981). But the competitive environment at the Department of Biology at Harvard seems to have pushed Wilson to find a more definitely authoritative tool to achieve a unified theory of animal social behavior.

The Sociobiologist as a “Mathematician Naturalist”

Since the 1930s, institutional and financial resources for biological science had been increasingly redirected away from natural studies, to fund what would be called “molecular biology”. Warren Weaver, head of the Natural Science Division within the Rockefeller Division, was instrumental in imposing the vision that biology should get its inspiration from physical sciences. In his view, “ecology was glorified natural history.” (Mitman 1992, 105) [28]. This stance, and the incontestable results achieved by molecular biologists, seriously threatened the future of animal studies in biology departments [29].

The atmosphere of these days at Harvard is nicely crystallized in an oft-quoted anecdote told by Wilson about the Department of Biology, which also hosted James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of the DNA in 1953:

One day at a department meeting I naively chose to argue that the department needed more young evolutionary biologists, for balance. At least we should double the number from one (me) to two … I proposed, following standard departmental procedure, that [a specialist in environmental biology] be offered joined membership in the Department of Biology. Watson said softly, ‘Are they out of their minds?’ ‘What do you mean?’ I was genuinely puzzled. ‘Anyone who would hire an ecologist is out of his mind,’ responded the avatar of molecular biology.

Naturalist (1994) pp. 219–220

Molecular biology had renewed the faith in reductionism, and made animal behaviorists studying whole organisms in the field look simply wrong headed. Complex social forms would be deciphered by looking at their putative genetic basis, which implied skills in physical chemistry (and the mathematical foundations it supposed) that most naturalists lacked. Wilson himself did not feel at ease with mathematics but was eager to catch up, sensing that in these “molecular wars”, naturalist studies could be saved by (and had no choice but) strengthening their scientific status by drawing on the prestige of some mathematical biology. As he puts it, the alternative was to be relegated in museums and looked down as mere “stamp collectors.”

After his encounter with Altmann and his reaction against behaviorism, this was another strong motive to work at a synthesis, aiming at preserving the naturalists’ credo and upgrading it to the required scientific standards of the day. Sociobiology would be the comparative study of the biological roots of social behavior where the wide knowledge of species and observation skills of the naturalists would be an asset, and a unifying theory of social behavior formulated in advanced mathematics expressions – providing an authoritative analytical framework on par with the scientific status of molecular biology.

The time was ripe for such an alliance between naturalists and mathematicians. Since the early twentieth century, population ecology had developed into a mathematical science. Inspired by the successes of differential calculus in physics and chemistry, mathematical formalisms had slowly been imported in biology to study problems in demography, epidemiology, and ecology (Kingsland 1995). Alfred Lotka (1880-1947) was an early promoter of this approach, and if he failed to reach true recognition outside demography in his lifetime, his work inspired many natural and social scientists in the post-war period.

One of them was ecologist G. E. Hutchinson, whose student Robert MacArthur became a collaborator of Wilson [30]:

Although [MacArthur] had majored in mathematics at Marlboro College, and had a conspicuous talent for it, his heart was in the study of birds. He was a naturalist by calling, and seemed happiest when searching for patterns discovered directly in Nature with the aid of binoculars and field guides. … As a mathematician-naturalist he was unique […].

Naturalist (1994) pp. 244 - our italics.

Hence in Wilson’s memory, what MacArthur chiefly brought to their collaboration was the ability to think about ecological problems as a physicist or mathematician, while retaining at heart an identity of a naturalist. This fitted perfectly Wilson’s agenda: to bring the physicist’ mechanist metaphor and mathematical sophistication to the rescue of naturalist studies.

However, models in population ecology focused on interspecies relationships, and remained silent on the more essential forms of social behavior observable at a lower, intra-species level. To account for the latter, Wilson followed a similar strategy: he relied on recent developments in mathematical modeling by the British naturalist William Hamilton (Segerstrale 2013), whose mathematical analysis of altruism in social insects had come to his attention. Hamilton provided a simple rule which reinterpreted diverse forms of social behavior among kin as the outcome of a cost-benefit Darwinian calculation at the gene level, with the benefits brought to inclusive fitness outweighing the costs to individual fitness borne by the performer of the altruistic act. This rule was presented using a maximization principle and sophisticated mathematical formalizations not typical of a naturalist’ training. It epitomized the values of abstract reasoning and generalization by the enunciation of laws in the tradition of mathematico-physics becoming ever more present in contemporary biology.

Thence, Hamilton’s rule helped reintroduce social behavior in the series of topics studied by modern biology. This gene-centered view of sociality also replaced the “survival of the species” brand of argument that had made Williams gasp. Naturalists had found a new legitimacy in concentrating their efforts on social groupings; they had reintegrated the orthodox Darwinian framework.

It is not often stressed that in addition to the presentation of his mathematical model, Hamilton’s papers contained a lengthy and technical discussion of its relevance for many instances of social species, supported by a wealth of observational studies (Hamilton 1964). The social aspects of behavior being most easily studied in the field, this comforted the naturalists in the position of main providers of the empirical material supporting mathematical models of sociality, and (especially if they agreed to train in math) as the most able to extend these models to a variety of situations. Indeed, beyond the presentation of elementary principles in theoretical population biology in its first chapters, Sociobiology provided an empirical validation of these principles by illustrating them with an encyclopedic survey of observational studies of social species [31].

Wilson followed a similar approach when he included the notion of evolutionary stable strategies (ESS), recently developed by George Price and John Maynard Smith (in close relation to Hamilton), among the mechanisms of social evolution presented in the first chapters of Sociobiology (Maynard Smith and Price 1973; Harman 2010; Wilson 1975, 129). An “evolutionary strategy” designates a highly stylized representation of a type of animal behavior in relation to conspecifics or to the broader environment, limited to a small repertoire of options (such as fight or flight) with associated payoffs, measured in terms of fitness. It is denoted as “stable” if the individuals adopting it and largely present in a population cannot be replaced by individuals adopting a different strategy.

Drawn from game theory, an interdisciplinary theoretical framework developed since the 1940’s by mathematicians, economists and biologists to model social interactions (Erickson 2015), the notion of ESS facilitates the study of how populations composed of animals adopting competing types of behaviors evolve, through the resolution of mathematical models or through simulations. These advantages come at the price of a de-contextualization of the behaviors under study, and a difficult transposition of the assumption made on the rationality of the human players to a game played by animals.

The un-natural assumption of rationality led even mathematically inclined biologists like Richard Lewontin and Richard Levins not to pursue their initial interest in game theory for animal behavior studies (Erickson 2015, 221–22). In contrast, Wilson provided a stage in Sociobiology for a dialogue between game theoretic and naturalist approaches to animal social studies. Game-theoretic models need the scaffold of field observations, both for the calibration of their parameters (definition of the types of behaviors and of the payoff matrix) and to gauge their external validity, as witnessed by the references to a number of naturalist studies in the original paper on ESS by Maynard Smith and Price. The fact that game theory was integrated in a synthesis of animal social behavior studies under the authority of naturalists bolstered the relevance of the latter in the competitive landscape of contemporary biology.

Conclusion

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis has been extensively studied for the debate it initiated on the relationships between natural and social sciences. This concentrates the historical significance of Wilson’s book on one type of synthesis which the book claimed to achieve: the sociobiology of all social animals, from ants to human beings, developed in its twenty-seventh chapter. In this study, we put the focus on a different kind of synthesis pursued by Sociobiology, recasting it in the continuity of two scientific projects bearing such a name, which developed in post-war United States.

We argued that animal social behavior was investigated by ecologists, ethologists and comparative psychologists, each characterized by different practices of places. In these fields, researchers with an inclination for the collection of observations in natural conditions were feeling an increasing pressure to assert the legitimacy of outdoor studies, perceived not to meet the standards of rigor of modern science. Scott’s CSASNC, which morphed into the Section On Animal Behavior and Sociobiology (forerunner of the Animal Behavior Society), was an organizational effort explicitly directed at promoting studies of animal behavior wedding techniques and protocols from the laboratory and the field.

Altmann developed his own sociobiology project while observing primates for two years on Cayo Santiago Island, a type of field station which the CSASNC had called to develop for allowing observations blending natural and controlled conditions. Altmann’s own version of sociobiology was still rooted in naturalist studies of animal behavior, but this time the deficit in legitimacy was not so much felt in relation to superior laboratory methods, than in regard to the reductionist program of molecular biology, which was so dominant in the immediate post-war period, especially at the Department of Biology at Harvard where Altmann was conducting his PhD under the sponsorship of Wilson. In this context, Altmann’s sociobiology developed by combining extensive field studies with a heavy emphasis on the mathematical analysis of information and communication in animal groups.

In the light of these two preceding episodes, Wilson’s sociobiology appears to follow a recurring pattern: the development of a defensive alliance between the naturalist approach to animal behavior studies and new forms of scientific endeavor threatening this naturalist tradition. While Scott was most concerned with laboratory settings replacing studies under natural conditions, Wilson risked to be sidelined by molecular biology, which favored sophisticated theoretical developments and a reductionist analysis of phenomena. Embracing these new developments by discussing them on par with classic studies of animal societies, as illustrated with the centrality of mathematical models of kin selection in Sociobiology, enhanced the relevance of the type of knowledge produced by naturalists: centrality of field work, attention to levels of social interaction at the group and interspecies level, and the study of evolutionary dynamics in broad, natural ecosystems [32].

In this frame, the historical meaning of sociobiology can be reconsidered: in addition to the “bombshell” effect of the book Sociobiology, sociobiology as a series of post-war projects also represented a more discrete but effective attempt to reaffirm the relevance of the naturalist tradition in animal behavior studies and biology at large.

References cited

Abir-Am, Pnina G. 1982. The discourse of physical power and biological knowledge in the 1930s: A reappraisal of the Rockefeller Foundation’s “policy” in molecular biology. Social Studies of Science 12: 341-382.

Abir-Am, Pnina G. 1987. The biotheoretical gathering, trans-disciplinary authority, and the incipient legitimation of molecular biology in the 30’s: New perspectives on the historical sociology of science. History of Science 25: 1-70.

Abraham, Tara H. 2004. Nicolas Rashevsky’s mathematical biophysics. Journal of the History of Biology 37: 333-385.

Alcock, John. 2001. The Triumph of Sociobiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Allee, Warder C. 1930. Concerning community studies. Ecology 11: 621-630.

Allee, Warder C., and Marjorie H. Allee. 1925. Jungle Island. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Allee, Warder C., Orlando Park, Alfred E. Emerson, Thomas Park, and Karl P. Schmidt. 1949. Principles of Animal Ecology. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Altmann, Stuart A. 1962. A field study of the sociobiology of Rhesus monkeys, Macca mulatta. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 102: 338-435.

Altmann, Stuart A. 1965. Sociobiology of rhesus monkeys. II. Stochastics of social communication. Journal of Theoretical Biology 8: 490-522.

Altmann, Stuart A. 1967. The Structure of Primate Social Communication. In Social Communication among Primates, ed. Stuart A. Altmann, 325-362. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Banks, Edwin M. 1985. Warder Clyde Allee and the Chicago school of animal behavior. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 21: 345-353.

Beach, Frank A. 1950. The snark was a boojum. American Psychologist 5: 115-124.

Bellomy, Donald C. 1984. Social Darwinism revisited. Perspectives in American History 1:1–129

Benson, Keith R. 1991. From museum research to laboratory research: The transformation of natural history into academic biology. in The American Development of Biology, ed. Ronald Rainger, Keith R. Benson, and Jane Maienschein, 49-83. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Billick, Ian, and Mary V Price, ed. 2010. The Ecology of Place: Contributions of Place-Based Research to Ecological Understanding. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borrello, Mark E. 2010. Evolutionary restraints: the contentious history of group selection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brockman, John. 1995. The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Burkhardt, Richard W. 1999. Ethology, natural history, the life sciences, and the problem of place. Journal of the History of Biology 32: 489-508.

Burkhardt, Richard W. 2005. Patterns of Behavior: Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and the Founding of Ethology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Burns, Lawton R. 1980. The Chicago School and the study of organization-environment relations. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 16: 342-358.

Calhoun, John B. 1950. The study of wild animals under controlled conditions. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 51: 1113-1122.

Candland, Douglas K., and Bryon A. Campbell. 1962. Development of fear in the rat as measured by behavior in the open field. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 55: 593-596.

Carpenter, C. R. 1934. A field study of the behavioral and social relations of howling monkeys (Alouatta palliata). Comparative Psychology Monographs 10: 1-168.

Cherry, Robert. 1980. Biology, sociology and economics - an historical analysis. Review of Social Economy 38: 141-154.

Chiszar, David. 1972. Historical continuity in the development of comparative psychology: Comment on Lockhard’s “Reflections.” American Psychologist 27: 665-667.

Collias, Nicholas E. 1991. The role of American zoologists and behavioural ecologists in the development of animal sociology, 1934-1964. Animal Behaviour 41: 613-631.

Coursen, Blair. 1956. Jungle laboratory: a visit to Barro Colorado Island. Turtox News 34: 138-146.

Dewsbury, Donald A. 1992. Comparative psychology and ethology: A reassessment. American Psychologist 47: 208-215.

Dietrich, Michael R. 1998. Paradox and persuasion: Negotiating the place of molecular evolution within evolutionary biology. Journal of the History of Biology 31: 85-111.

Emlen, John T. 1996. Adventure Is Where You Find It: Recollections of a Twentieth Century American Naturalist. Privately published.

Erickson, Paul H. 2015. The World the Game Theorists Made. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Finnegan, Diarmid A. 2008. The spatial turn: Geographical approaches in the history of science. Journal of the History of Biology 41: 369–388.

Gibson, Abraham H. 2012. Edward O. Wilson and the organicist tradition. Journal of the History of Biology 46: 599-630.

Hagen, Joel. 1999. Naturalists, molecular biologists, and the challenges of molecular evolution. Journal of the History of Biology 32: 321-341.

Hamilton, William D. 1964. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I and II. Journal of Theoretical Biology 7: 1-16, 17-52.

Haraway, Donna J. 1981. The high cost of information in post-World War II evolutionary biology: ergonomics, semiotics and the sociobiology of communication systems. Philosophical Forum 13: 244-278.

Haraway, Donna J. 1983. Signs and dominance: From a physiology to a cybernetics of primate society. Studies in the History of Biology 6: 129-219.

Haraway, Donna J. 1989. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. London: Routledge.

Harman, Oren S. 2010. The price of altruism: George Price and the search for the origins of kindness. New York: W.W. Norton.

Hodos, William, and C. B. G. Campbell. 1969. Scala naturae: Why there is no theory in comparative psychology. Psychological Review 76: 337-350.

Holmes, S. J. 1922. A tentative classification of the forms of animal behavior. Journal of Comparative Psychology 2: 173-186.

Jaynes, Julian. 1969. The historical origins of “ethology” and “comparative psychology.” Animal Behaviour 17: 601-606.

Johnson, Kristin. 2008. The return of the phoenix: The 1963 International Congress of Zoology and American zoologists in the twentieth century. Journal of the History of Biology.

Kay, Lily E. 1996. The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology. Oxford University Press.

Keller, Evelyn F. 2002. Making Sense of Life: Explaining Biological Development with Models, Metaphors, and Machines. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kingsland, Sharon E. 1995. Modeling Nature: Episodes in the History of Population Ecology. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kitcher, Philip. 1985. Vaulting Ambition: Sociobiology and the Quest for Human Nature. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kohler, Robert E. 1976. The management of science: The experience of Warren Weaver and the Rockefeller Foundation programme in molecular biology. Minerva 14: 279-306.

Kohler, Robert E. 1991. Partners in Science: Foundations and Natural Scientists, 1900-1945. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kohler, Robert E. 2002. Landscapes & Labscapes: Exploring the Lab-Field Border in Biology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Krebs, John R. 1976. Review of “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.” Animal Behaviour 24: 709-710.

Lehrman, Daniel S. 1953. A critique of Konrad Lorenz’ s theory of instinctive behavior. Quarterly Review of Biology 28: 337-363.

Lerner, Richard M. 1992. Final Solutions: Biology, Prejudice, and Genocide. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Lightman, Bernard V. 2016. A Companion to the history of science. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Livingstone, David N. 1995. The spaces of knowledge: contributions towards a historical geography of science. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13: 5 – 34.

Lown, Bradley A. 1975. Comparative psychology 25 years after. American Psychologist 30: 858-859.

Maier, N. R. F., and T. C. Schneirla. 1935. Principles of Animal Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mason, William A. 1980. Minding our business. American Psychologist 35: 964-967.

Maynard Smith, John, and George R Price. 1973. The logic of animal conflict. Nature 246: 15-18.

Mitman, Gregg. 1992. The State of Nature: Ecology, Community, and American Social Thought, 1900-1950. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mitman, Gregg. 1996. When nature is the zoo: Vision and power in the art and science of natural history. Osiris 11: 117-143.

Montgomery, Georgina. 2005. Place, practice and primatology: Clarence Ray Carpenter, primate communication and the development of field methodology, 1931–1945. Journal of the History of Biology 38: 495-533.

Myers, Greg. 1990. Every Picture Tells a Story: Illustrations in E. O. Wilson’s Sociobiology. In Representation in Scientific Practice, ed. Michael Lynch and Steve Woolgar, 231-265. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nowak, Martin A., Corina E. Tarnita, and Edward O. Wilson. 2010. The evolution of eusociality. Nature 466: 1057-1062. doi:10.1038/nature09205.

Paul, Diane B. 1998. The Politics of Heredity: Essays on Eugenics, Biomedicine, and the Nature-Nurture Debate. New York: State University of New York.

Rader, Karen A. 2004. Making Mice: Standardizing Animals for American Biomedical Research, 1900−1955. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ramsden, Edmund, and Jon Adams. 2009. Escaping the laboratory: The rodent experiments of John B. Calhoun & their cultural influence. Journal of Social History 42: 761-792.

Rawlins, Richard G., and Matt J. Kessler. 1986. The History of Cayo Santiago Colony. In The Cayo Santiago Macaques: History, Behavior & Biology, ed. Richard G. Rawlins and Matt J. Kessler. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Rees, Amanda. 2006. A place that answers questions: primatological field sites and the making of authentic observations. Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 37: 311-333.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1975. Social Darwinism. Newsweek 86: 55.

Schneirla, T. C. 1933. Studies on army ants in Panama. Journal of Comparative Psychology 15: 267-299.

Schneirla, T. C. 1938. A theory of army-ant behavior based upon the analysis of activities in a representative species. Journal of Comparative Psychology 25: 51-90.

Schneirla, T. C. 1946. Contemporary American Animal Psychology in Perspective. In Twentieth Century Psychology, ed. P. L. Harriman, 306-316. New York: Philosophical Library.

Scott, J. Paul. 1947. Formation of a Committee for the Study of Animal Societies under Natural Conditions. Ecology 28: 207-208.

Scott, J. Paul. 1950. Foreword to “Methodology and techniques for the study of animal societies.” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 51: 1003-1005.

Scott, J. Paul. 1985. Investigative Behavior: Toward a Science of Sociality. In Studying Animal Behavior: Autobiographies of the Founders, ed. Donald A. Dewsbury, 389-429. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press.

Scott, J. Paul. 1989. The Evolution of Social Systems. New Yor: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

Segerstrale, Ullica. 2000. Defenders of the Truth: The Sociobiology Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Segerstrale, Ullica. 2013. Nature’s Oracle: The Life and Work of W. D. Hamilton. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shmailov, Maya. 2016. Intellectual Pursuits of Nicolas Rashevsky: the Queer Duck of Biology. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Tobach, Ethel. 2000. T.C. Schneirla: Pioneer in Field and Laboratory Research. In Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology: Volume IV, ed. Gregory A. Kimble and Michael Wertheimer, 215-233. Philadelphia: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Trivers, Robert L. 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology 46: 35-57.

Trivers, Robert L. 1974. Parent-offspring conflict. American Zoologist 14: 249-264.

Weidman, Nadine. 1996. Psychobiology, progressivism, and the anti-progressive tradition. Journal of the History of Biology 29: 267-308.

West Eberhard, Mary J. 1976. Born: Sociobiology. Quarterly Review of Biology 51: 89-92.

Wilson, Edward O. 1962. Chemical communication among the workers of the fire ant. Animal Behaviour 10:134–164.

Wilson, Edward O. 1975. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, Edward O. 1994. Naturalist. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Wright, Sewall. 1945. Tempo and mode in evolution: A critical review. Ecology 26: 415-419.

Wynne-Edwards, Vero C. 1962. Animal Dispersion in Relation to Social Behavior. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.